Mutt or Mongrel?

- Fileve Tlaloc

- Nov 12, 2025

- 8 min read

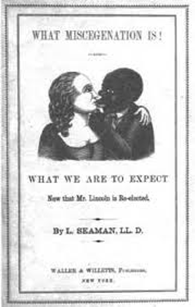

What is the meaning of mongrel or mutt? Are they synonyms or does each word have its own definition or connotation? As a person with dual nationality who is of “mixed race,” I have come across these words since I was a child. Discussions of race were common in my household growing up. My father being a Euro-American of German-Sicilian descent and my mother being a South African "Coloured" of African, Asian, and European descent conversations of racial politics often filled the household. On many occasions the word “mutt” would be strewn about. One relative or another would claim to be a "mutt," because they were mixed in some way or another. I reencountered the term when doing my dissertation research on Coloured identity in post-Apartheid South Africa. I do not, however, recall anyone referring to themselves as a "mongrel" since it was offensive as exemplified in the above propaganda print.

Examination of the etymology of both terms show that while both refer to a hybrid or mixed breed of plant or animal, one became more acceptable than the other, perhaps because of how each were used in popular culture. While the use of mutt is traced back to 1899 in the first recorded written use, according to the etymology of the word, "mongrel" comes from mid-15th century Old English *gemong meaning "to mingle," which stems from the Proto-Germanic root of mag - "to knead or mix." The modern English word among meaning "in the midst of" is related. In the mid-1400s, the addition of the diminutive and/or deprecatory suffix -rel from Old French gave rise to the new word "mongrel." The word could be applied to anything that was a mix of two kinds of like things and gained in popular use in animal husbandry to the benefit of heritable traits. For instance, mongrel offspring differ from pure breeds in that they are not considered as valuable. Their lineage tainted. Their heritable physical and behavioral attributes considered questionable and left up to the gamble of nature. The physical traits from generation to generation of a mixed-breed would be highly variable unlike the stable physical features and temperament of a pure-bred.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word was applied to human beings in a derogatory way referencing both physical and behavioral characteristics beginning in the 1590s. Human beings are animals and as such these ideas were applied to humans as well. If we examine the correlation of the popularity of the word mongrel and historical context of chattel slavery and race science (at least in the United States and other English-speaking nations) we can see that the use of the word peaked in the 1880s not long after slavery was abolished in the United States and people of color were beginning to assert their full citizenship rights.

But let's get back to the term mutt. In the early 1900s the term mutt began to take root in the common people's lexicon. Its first documented use was in 1899 and is said to be an abbreviation of "mutton head" referring to someone of low intellect. The word was designated to canines, humans, and racehorses of low intelligence, skill, or attractiveness. In 1907 a comic strip created by Budd Fisher called "Mutt & Jeff" was featured in the sports section of the San Francisco Chronical near the horse race section. Mr. Fisher an avid gambler featured many stories surrounding the races to the entertainment of his readers.

Perhaps this is pure conjecture on my part but there seems to be a correlation with popularity of the cartoon with the use of the word mutt.

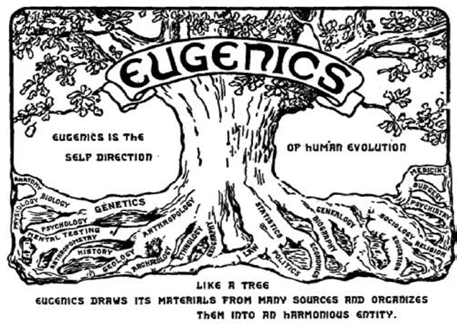

Whatever the reason for acceptability to use one word over the other, it is clear that ideas of breeding and heritable attributes can be controlled and organizations sprang up with the intent to "better the breed" whether canine, equine or human.

The idea that behavioral attributes can be bred for permeates people's ideas about domestic animals and people. For instance, Labrador Retrievers are supposed to be even-tempered family dogs, whereas Akitas were bred for their brave independence and loyalty. These ideas were and continue to be promoted through the Westminster Kennel Club and later the American Kennel Club (to name a few), which had ties to eugenics movements of the 1800s.

Where do these ideas of breeding come from and what does it matter? Why am I even writing about dogs in relation to human beings? In part human beings and canines have a long history of cohabitation of at least 20,000 years. Some say it is because of this relationship that human beings have been able to develop culturally in the ways that we have been. Canines helped us hunt and travel, they carried things, protected us and our property, and provided companionship.

With that said, the idea of acceptable breeds that were recorded came with the creation of formal organizations whose members were also proponents of Eugenics Movements. They used canines (and other domestic animals) as examples of good breeding versus bad.

For instance, Sir Francis Galton published Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development in 1883 in part influenced by his cousin, Sir Charles Darwin's work Origin of the Species. Galton, a proponent of the principles of animal husbandry as applied to human beings. He stated:

"My general object has been to take note of the varied hereditary faculties of different men, and of the great differences in different families and races, to learn how far history may have shown the practicability of supplanting inefficient human stock by better strains, and to consider whether it might not be our duty to do so by such efforts as may be reasonable, thus exerting ourselves to further the ends of evolution more rapidly and with less distress than if events were left to their own course” (Galton 1883; p. 1).

We must free our minds of a great deal of prejudice before we can rightly judge of the direction in which different races need to be improved. We must be on our guard against taking our own instincts of what is best and most seemly, as a criterion for the rest of mankind. The instincts and faculties of different men and races differ in a variety of ways almost as profoundly as those of animals in different cages of the Zoological Gardens; and however diverse and antagonistic they are, each may be good of its kind (p. 2).

The investigation of human eugenics—that is, of the conditions under which men of a high type are produced—is at present extremely hampered by the want of full family histories, both medical and general, extending over three or four generations. There is no such difficulty in investigating animal eugenics, because the generations of horses, cattle, dogs, etc., are brief, and the breeder of any such stock lives long enough to acquire a large amount of experience from his own personal observation. A man, however, can rarely be familiar with more than two or three generations of his contemporaries before age has begun to check his powers; his working experience must therefore be chiefly based upon records. Believing, as I do, that human eugenics will become recognised before long as a study of the highest practical importance, it seems to me that no time ought to be lost in encouraging and directing a habit of compiling personal and family histories. If the necessary materials be brought into existence, it will require no more than zeal and persuasiveness on the part of the future investigator to collect as large a store of them as he may require” (Galton 1883, p. 30-31)

AKC recognized breeds differs from 400-1000 globally recognized breeds. Humans are divided into 5 racial categories. Both numbers have varied over time and are of socially constructed. Racial categories are based partly on ancestral/inherited DNA and more than geographically patterned morphological variation like skin color than dog breeds. "Analogy between races and dog breeds incorrectly privileges biology over the social and historical factors that have led to the development of racial constructs" (Norton et al. 2019, p. 2).

Members of these clubs were able to determine and formalize which breeds were worth classifying as "pure" and which would be excluded. Mixed-breed dogs or "mutts" were considered inferior due to the genetic variation. The irony is that genetic variation of the mutt is actually healthier than the pure-bred dogs - hybrid vigor.

The goal here is to reveal why equating race to dog breeds is racist despite popular belief that it is logical. Counter the belief that because dogs are distinguishable on sight by breed, human racial categories are likewise biologically based on arbitrary superficial biology, what can be seen such as skin, hair, and eye color, body or eye shape, or hair texture. Breeds arise due to breeders’ extreme control of mating to maximize the presence of desired heritable traits in the next generation of dogs. Races arise based on the geographic isolation or proximity. In both cases all breeds and races are able to reproduce with each other within their own species. Hierarchical ranking of human races is also inherently competitive, which is just one reason why outdated, and overly simplistic conceptions of evolutionary biology have historically paired with racism and still do. Since 1493 and the advent of maritime and transportation technologies that allowed flora and fauna (including humans) greater movement and interbreeding, interspecies breeding occurred. For purists and people concerned with social Darwinism creating ways of control was paramount to the betterment of society and progress.

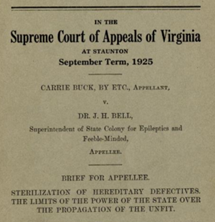

We do not have to look far to see how these ideas of breeding and eugenic in relation to canines have permeated our legal and social framework in the United States to the detriment of our citizens. In 1924, Virginia was the first state to codify antimisegenation laws prohibiting race-mixing under penalty of the law. This set the legal framework for further disenfranchisement and removal of human agency with regard to mate selection and reproduction. By the 1950s over half of the union had similar laws in place. Virginia continued the legal attack on reproduction in the name of eugenics when in 1925 the supreme court case was brought against Carrie Buck. She became the first woman to officially be sentenced to an institution and forcibly sterilized because it was feared her poor mental capacity was heritable through subsequent generations.

The 1828 edition of Webster’s dictionary defined “cur" or "mongrel" as “a degenerate dog; and in reproach, a worthless man.” Rather than apply the lessons learned from past transgressions of both canines and humans to redefine what “better breeding” might mean in this day and age, the dog fancy behaves as though nothing has changed since the nineteenth century, and that nonhuman animals aren’t subject to the same laws of biology as humans. The forced sterilization of women of color and people with mental and physical disabilities, the institutionalization of people that did not fit the ideals of the time have yet to be fully reckoned with as we move toward the continued villanization and dehumanization of people in the United States who do not fit the ideals of the old ways of thinking. Likewise, institutions, clubs, and people continue to promulgate ideas about acceptable dog breeds and breed specific legislation continues to be proliferated without critical thinking. It is for this reason I took on the work to unpack these ideas in the creation of a series of ceramic sculptures titled, "What are you: Dehumanizing Racial Ideologies."

Comments